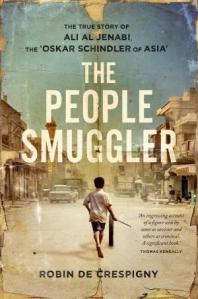

Review of The People Smuggler, by Robin de Crespigny, Penguin, 2012

Mark Goudkamp, Refugee Action Coalition

IT IS December 2010. After finally being released from the Villawood detention centre, a refugee and his mother watch TV in horror as an asylum boat smashes into the rocks off Christmas Island.

He follows the ‘debate’ that follows, where ‘evil people smugglers’ are blamed, and Julia Gillard and Chris Bowen coin the phrase: the people smugglers’ business model.

“They declare they are going to smash this mysterious identity by any means. I laugh out loud when I hear it. Do they think there are men in suits sitting around boardroom tables somewhere devising strategies? Has no one told them people smuggling is an amorphous rag-tag network run by word of mouth and mobile phones? There are no records or bank accounts. No spreadsheets or business plans. They pop up wherever people are trying to escape and disappear when they are no longer needed.”

“They declare they are going to smash this mysterious identity by any means. I laugh out loud when I hear it. Do they think there are men in suits sitting around boardroom tables somewhere devising strategies? Has no one told them people smuggling is an amorphous rag-tag network run by word of mouth and mobile phones? There are no records or bank accounts. No spreadsheets or business plans. They pop up wherever people are trying to escape and disappear when they are no longer needed.”

Ali Al Jenabi’s words come at the end of The People Smuggler, the epic life story of this Iraqi refugee turned smuggler. Originally conceived as a film, Robin de Crespigny’s wonderfully written book projects Ali’s brave and authentic voice in a way that is captivating and compelling.

The book is subtitled “The Oskar Schindler of Asia”—referring to the German industrialist who saved many Jewish lives by employing them in his factory at the height of the Holocaust. But unlike Schindler, Ali himself has to flee persecution, and in many ways his story is even more convincing.

Ali’s odyssey is full of both personal tragedy and political insight, and his contagious sense of humour despite immense ups and downs also makes it entertaining. Written in the first person, the book invites the reader to travel in Ali’s shoes and to ask themselves ‘what would I do in the same situation?’.

If MPs and media commentators bother to read it, many will be forced to hang their heads in shame—firstly for the myths they eagerly promote about people smugglers (each and every one of which Ali shows up as fanciful and politically motivated); and secondly for the cruel and vindictive treatment Ali has received at the hands of successive Australian governments since his extradition.

The book is divided into three main stages: Iraq (1970-1999); Indonesia (1999-2003); and Australia (2003-2011)—and thankfully it includes useful maps of the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Ali’s childhood in 1970s Iraq is cut short when he assumes paternal responsibility for his six younger siblings. His outspoken father had been arrested, detained, and released a broken man. Following Saddam Hussein’s crackdown on the Shia uprising in 1991—which the US abandons—Ali is sent to Abu Ghraib prison. His harrowing description of doing time there alone ought to be enough to soften even the most hardened anti-asylum seeker heart.

Upon his release, Ali heads to Iraqi Kurdistan to work for the resistance. He hopes a popular revolution can bring down Saddam, but is soon disillusioned:

“It is becoming clear that the movement is driven not by patriotism but finance, and is divided because there are so many different interests bankrolling each party. The Iranian intelligence, the American CIA, the UK, Syria, are all in there with big money.”

After a plot to kill Saddam fails and the regime starts wiping out the resistance, Ali’s only option is to flee. His attempt to reach Europe ends disastrously, when his group is caught in Istanbul and deported.

Yet Ali is desperate to reunite with his mother and siblings—some of whom have fled to Qom in Iran without him. He and his friend Mustafa hire Fadi—“a tough, swarthy Kurdish Iranian”—for US$200. They are broke, but Fadi accepts the $50 they have upfront, trusting them to pay the remainder on arrival (so much for Kevin Rudd’s “vilest form of human life!”). Ali writes: “I wish I had more to give him extra. I had misjudged him. He is wily, diligent, clever and professional. Getting us here seems to matter to him more than the money. ‘Thank you,’ I say, shaking his hand with admiration and respect. ‘You are some smuggler.’”

In Iran, after meeting an Iraqi who has successfully applied for refugee status via the UNHCR in Pakistan, Ali is eager to pursue this option for the whole family.

“At last we have found the right way to do things…It is liberating to feel we are following the correct procedure and it make me realise the toll it has taken to be always on the wrong side of the law”.

Yet after seven months of waiting and with a growing fear that the thaw in Iran-Iraq relations might land them back at Saddam’s feet, he travels to the UN office in Pakistan to check their application. But on the way, he is told: “Forget it, it’s like a lottery. You will never get there if you try to do it the right way, my friend”.

So Ali heads to Indonesia to try and get to Australia but is betrayed and left on the beach when the boat he’d paid for a spot on sails without him. When offered a deal by the same people smuggler—to put one of his family on each boat for free if he works for the smuggler—he accepts as it is the only way to get his family out. But he soon realises he can do it better.

“My mind keeps returning to the calls on Omeid’s phone from desperate Iraqis, their families torn apart, trying to escape Saddam like I had. If you empathise with these people’s plight, refuse to play games, and really want to help them, the job wouldn’t be too hard.”

Ali’s operation is far from the picture of criminal smuggling syndicates that our politicians speak of. Children travel half price or free on Ali’s boats, and (like Fadi who smuggled him into Iran) he is often giving passengers greatly discounted rates with promises of the remainder on arrival.

He gets seven boats successfully to Australia. But by now it’s 2001, when John Howard’s “increased hostility” towards asylum seekers is in overdrive. Interpol are after him, and the AFP’s boat disruption operations are more aggressive. They ask Haidar, one of Ali’s employees, to spy on him: “Great”, Ali replies. “Spy on me. Give them the right details, just the wrong days”.

With the noose rapidly tightening, some less scrupulous smugglers take risks to get those in limbo out quickly. The overcrowded SIEV-X of Abu Qassey goes down, and Ali’s boat, which departed a day earlier, is intercepted and towed back to Lombok by the Australian Navy. He sends the returnees $4000 but can do little else as he goes into hiding.

Ironically, it is when a friend asks him to come to Bangkok to be a partner in his expanding restaurant that he is caught. Unlike Indonesia, Thailand has laws against people smuggling, and somehow the AFP are waiting for him on arrival.

After almost a year in a Thai jail cell that reminds him of Abu Ghraib, Ali is sent to be tried in Darwin. When strip-searched, he remarks: “Even in Abu Ghraib, you were only stripped for torture.” But this pales compared to the 35 years he might face under Australia’s people smuggling laws, which mandate five years per boat.

“I am the first smuggler to be extradited to Australia, and the government will prove how despicable I am by the money I have made out of human misery. They are evidently saying I charged $US10000 per person, which is laughable when I think of how many came for less than a thousand, or on promises that were never paid…”

It is a twisted irony that at the time of the invasion of Iraq, Ali is rotting in an Australian jail: “We have lived under Saddam’s repression for over two decades without any show of concern from the West…And who is going to take the wave of refugees the war in Iraq will create? Not Australia, according to him (Howard). He claims he has stopped the boats.”

At Ali’s committal hearing, 108 of his former passengers are flown in to testify against him. But while they identify him, their testimonies don’t match up to the orchestrated campaign of demonisation run by parliament and the media.

However, in sentencing, Justice Mildren accepts that Ali “was not solely motivated by money, but was largely motivated by the need to get his family to Australia come what may”.

Shamefully after nearly two years in Villawood Ali is released by the now Labor Immigration Minister Chris Evans on a Removal Pending Bridging Visa—a decision which his successor Chris Bowen has endorsed and which applies to this day.

Ali and Robin have spent the last three years digging up every detail of Ali’s remarkable life. Launched at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, it was highly ironic that in the session that followed them, Kevin Rudd launched the book of someone with genuinely vile ideas—Bob Katter.

“Stopping the boats” hurts asylum seekers and there is often no other way for them to reach safety other than to seek out unauthorised travel agents like Ali. And if such voyages were decriminalised, it would make their passage far safer.

Despite the constant barrage of anti-people smuggling rhetoric, there has been an outpouring of concern for the hundreds of Indonesian asylum boat crew held in Australian jails. The more widely Ali’s story is read, the better the placed the refugee movement will be to campaign against the demonisation of smugglers like Ali, Hadi Ahmadi and others, and to start challenging Australia’s people smuggling laws.

And let’s hope that it’s not too long before we can see Ali’s story on the big screen.