As part of its deal to send refugees to Cambodia, the Australian government has produced a ‘factsheet’ promoting the ‘opportunities’ available to people who take up their offer. Minister Dutton has also appeared in a video spruiking his deal. Both include outright lies and misrepresent the real situation for people living in one of the poorest countries in Asia.

Economy

Dutton claims Cambodia has a ‘stable economy’. Last year, Cambodia’s gross domestic product per person was just US$3,300 after adjusting for the cost of living (i.e., in purchasing power parity terms).

This makes it the 48th poorest country in the world; poorer than Nauru, Bangladesh and Burma. Its economy was devastated between 1975 and 1978 under the Khmer Rouge. It now largely depends on textiles, tourism and agriculture.

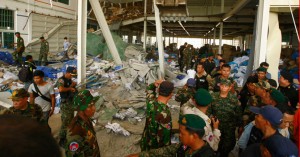

The textile industry accounts for over 70 per cent of exports and essentially exists to exploit the availability of cheap labour. The sector’s minimum wage is $US128 per month, just $8 above the official poverty line. Working hours are long and conditions are dangerous: two-thirds of factories have excessive heat levels, just 30 per cent provide their workers with sanitary drinking water, and fewer than 20 per cent of factories limit overtime to less than 2 hours a day.

One academic study describes the owners of Cambodia’s textile factories as overwhelmingly ‘nomads, moving from country to country, seeking low-wage employment markets and other mechanisms for producing at the lowest cost’.

Last year two workers died when two factories in Phnom-Penh collapsed. Six wage protesters and bystanders were killed by security forces in November 2013 and January 2014, and 25 others were imprisoned. Yet Minister Dutton describes life in Cambodia as ‘free from persecution’.

Nevertheless for many a job in the textile industry is probably their best alternative. In 2011, 41 per cent of Cambodians lived on less than US$2 a day at 2005 prices (a definition of extreme poverty used by the World Bank). Poverty is particularly severe among the 80 per cent of Cambodians who live in rural areas.

Health care

The government’s document claims healthcare is ‘of good quality for the region’, and that ‘Cambodia has a high standard of health care’. In fact life expectancy in Cambodia at birth is only 64; this ranks it at 180th in the world. This is worse than life expectancy in Nauru, Papua New Guinea and Burma.

There is an average of one doctor for every 4,300 people; around the same level as Afghanistan (in Australia there is one doctor for every 300 people). In South East Asia, only Indonesia and Laos have worse figures. There is only one hospital bed for every 1,400 people, which is fewer than everywhere in the region except Burma.

The Australian government’s own Smartraveller website explains that ‘health and medical services in Cambodia are generally of a very poor quality and very limited in the services they can provide’.

Only 71 per cent of people have access to clean, running water, and just 37 per cent have access to proper sanitation. The degree of risk of major infectious diseases is described as ‘very high’ by the US CIA, and bacterial diarrhoea, hepatitis A, and typhoid are major problems, along with dengue fever and malaria.

The prevalence of HIV / AIDS among adults is 0.74 per cent, which is the 50th worst in the world and worse than the figure for PNG.

Contrary to the government’s claim that Cambodia ‘does not have problems with stray dogs’, an estimated 800 people per year die of rabies. The incidence of dog bites in rural Cambodia is ‘the highest documented’ according to one academic study.

Education and conditions for children

Cambodia has the highest rates of child labour in all of East and South-East Asia. 39 per cent of children aged 5 – 14 have to work, most in the agricultural sector. Over 10,000 children per year suffer a work-related injury, and five out of every nine child labourers are engaged in what the ILO defines as ‘hazardous labour’. It is legal for children as young as 12 to perform domestic labour. 37 per cent of children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition.

Cambodia has one of the worst records for child trafficking and prostitution. Children are routinely trafficked from smaller villages to larger cities and to Thailand and Malaysia to work as domestic servants, street vendors, in factories, as prostitutes or to beg. Cambodia is notorious as a destination for child sex tourism.

US AID describe Cambodia’s education indicators as ‘among the lowest in Asia’. Only 34 per cent of children are enrolled in lower secondary education and 21 per cent in upper secondary education. 26 per cent of the population aged over 15 can’t read and write.

Political situation

Cambodia has been ruled by Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) for more than 25 years. Hun Sen is a former Khmer Rouge commander. His government is heavily dependent on foreign aid, which provides over half the state’s revenue.

The last national elections in 2013 were widely seen as rigged, and were ranked 4th worst out of 73 elections held worldwide around that time by one study. The election sparked mass protests against the government. In January 2014 these were banned by the government and security forces killed at least seven people. According to Human Rights Watch:

Since the CPP has been in power, members and commanders of government security forces have enjoyed impunity from investigation, let alone prosecution, for serious human rights abuses, including political assassinations, other extrajudicial killings, and torture. Instead, politically partisan police, prosecutors, and judges pursued at least 87 trumped-up cases against CNRP leaders and activists, members of other opposition political groups, prominent trade union figures, urban civil society organizers, and ordinary workers from factories around Phnom Penh.

Yet the government’s document claims there is ‘freedom of speech’ in Cambodia.

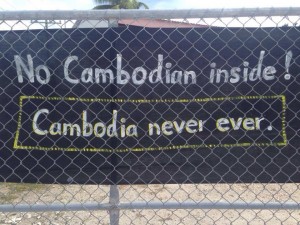

Dutton describes Cambodia as a ‘blend of nationalities’ and a ‘diverse nation’. In fact 90 per cent of the population is of Khmer ethnicity, and 96 per cent speak the Khmer language. The next largest ethnic group is Vietnamese (5 per cent). 97 per cent of the population are Buddhist. This lack of ethnic diversity is largely the result of genocidal policies pursued by the Khmer Rouge.

Crime and safety

The factsheet issued to refugees also claims that ‘Cambodia is a safe country, where police maintain law and order. It does not have problems with violent crime’. Again this is contradicted by information supplied to travellers by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which warns:

Assaults and armed robberies against foreigners have occurred, and foreigners have been seriously injured and killed… Foreigners have been the target of sexual assault in Cambodia. Due to the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, victims of violent crime, especially rape, are strongly encouraged to seek immediate medical assistance. The level of firearm ownership in Cambodia is high, and guns are sometimes used to resolve disputes. There have been reports of traffic disputes resulting in violence involving weapons. Bystanders can get caught up in these disputes. Foreigners have been threatened with handguns for perceived rudeness to local patrons.

Refugee protection

Cambodia is a signatory to the Refugee Convention. Despite this it has a record of human rights abuses and a record of failing to uphold the rights of asylum seekers and refugees within its borders. In 2009, Cambodia deported Uighur asylum seekers back to persecution in China. As recently as February 2015, Cambodia sent 36 Christian Montagnard asylum seekers back to Vietnam.

No foreign refugee living in Cambodia has even gained permanent residency let alone citizenship. Refugees have to hold a resident’s card for seven years before they are eligible for citizenship, but not one resident’s card had ever been issued to a refugee.

Cambodian NGOs oppose deal

Many Cambodian NGOs oppose the deal with Australia to resettle refugees from Nauru in Cambodia. On 17 October 2014, a 1000 strong demonstration of Cambodians, monks, students, victims of land eviction and representatives of unions and non-government organisations presented a petition to the Australian and Cambodian government calling for the abolition of the refugee resettlement deal.

Sister Denise Coghlan from the Jesuit Refugee Service told The Australian, ‘There are 65 to 70 refugees already here but the Cambodian government already cannot fulfil its obligations to them.’

Produced May 2015